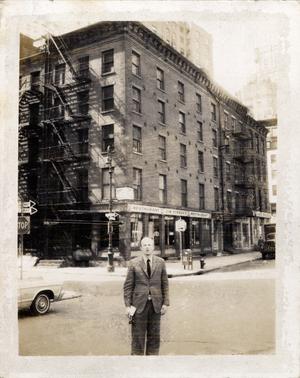

Rosenquist outside his studio at 3–5 Coenties Slip (third-floor corner), New York, 1960.

1960

In June, Rosenquist marries textile designer Mary Lou Adams, whom he had met while painting Times Square billboards. He is featured in the United Press International article “Billboard Painter, Local 230, Is Broadway’s Biggest Painter.” Ray Johnson introduces him to painters Agnes Martin and Lenore Tawney, who live and work in Lower Manhattan. Rosenquist quits working for Artkraft Strauss Sign Corporation after two fellow painters fall from scaffolding and die. He rents the studio that had been Martin’s at 3–5 Coenties Slip, near the workspaces of Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jack Youngerman, and commits himself to a career in fine art. He shares his studio space with Charles Hinman for part of the year. At Coenties Slip, Rosenquist begins creating paintings, such as Zone (1960–61), that incorporate commercial sign-painting techniques as well as images of people and products derived from advertisements and photographs. With the financial backing of Robert and Ethel Scull, Richard Bellamy—who

will become Rosenquist’s first dealer—opens the Green Gallery in New York in October with the exhibition Mark di Suvero.

1961

Several art dealers pay visits to Rosenquist’s Coenties Slip studio, including Richard Bellamy, Leo Castelli with his gallery manager Ivan Karp, Ileana Sonnabend, and Allan Stone. Henry Geldzahler, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and several private collectors also come. Stone offers Rosenquist an exhibition with Robert Indiana, which both artists turn down. Rosenquist makes his first sale with Robert Scull’s purchase of The Light That Won’t Fail II (1961). Scull is president and owner of a large fleet of New York taxicabs: Super Operating Corporation. He will become one of the largest private collectors of 1960s Pop art and a Rosenquist enthusiast. In October a photograph of Rosenquist painting The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961) appears on the cover of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Sunday Pictures magazine. Rosenquist meets critic Gene Swenson, whose sympathetic interviews with him and others associated with Pop art will help legitimize their work within the art world.

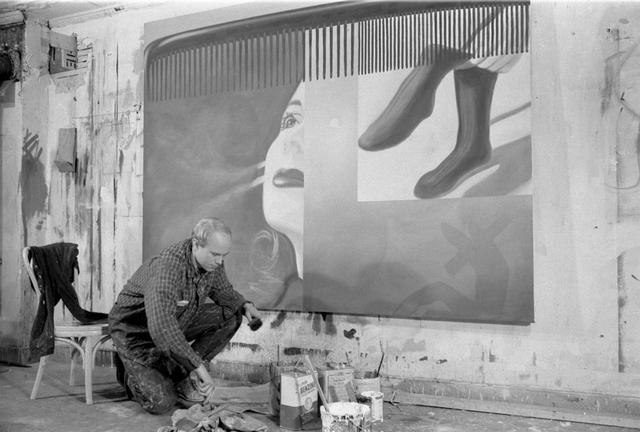

Rosenquist working on The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961), Coenties Slip studio, New York, 1961. Photo by Paul Berg.

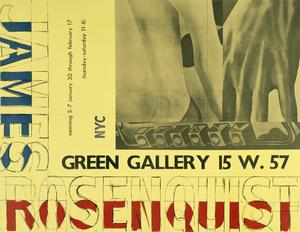

Poster designed by Rosenquist showing Pushbutton, 1961, for his exhibition at Green Gallery, New York, January 30 – February 17, 1962.

1962

In many works painted this year, such as Untitled (Two Chairs), Capillary Action, and Untitled (Blue Sky), Rosenquist attaches small rectangular or circular canvases to the surface of the larger paintings. He produces his first print, Certificate, a small photoengraving and etching for inclusion in the fifth volume of Italian gallerist Arturo Schwarz’s portfolio International Anthology of Contemporary Engraving: The International Avant-garde: America Discovered. Billy Kluver selects the works for the portfolio.

The Green Gallery, New York, presents Rosenquist’s first solo show, opening in January, for which the artist designs a poster featuring his painting Pushbutton (1961). The exhibition, organized by Richard Bellamy, sells out. Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, an early collector of Pop art, purchases three paintings: Pushbutton, Air Hammer (1962), and Waves (1962). In March, Art International publishes Max Kozloff’s “‘Pop’ Culture, Metaphysical Disgust, and the New Vulgarians,” one of the first articles linking Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Rosenquist together as a group. In April, Rosenquist’s Shadows (1961) is included alongside works by Dine, Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, and Robert Rauschenberg in the exhibition 1961 organized by Douglas MacAgy at the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts. In September, Gene Swenson’s article “The New American Sign Painters” is published in Art News, which associates Rosenquist with Dine, Robert Indiana, Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. In the fall Rosenquist’s work is included in Art 1963: A New Vocabulary, organized by Billy Kluver for the Fine Arts Committee of the Philadelphia YM/YWHA Arts Council; other artists represented include Dine, Johns, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, George Segal, and Jean Tinguely. Instrumental in recognizing the significance of the young artists who will be identified as “Pop artists,” Kluver, a scientist at Bell Labs, will organize several early exhibitions featuring their work. Rosenquist’s work is represented in seminal exhibitions at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York and the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. The title of the exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, International Exhibition of the New Realists, galvanizes the name “New Realists” for the American and British artists, who are represented alongside the work of the continental Europeans known as the Nouveaux Realistes. “New Realism” would shortly be replaced by “Pop art,” a term critic Lawrence Alloway had used to identify the work of several British artists who incorporated the imagery of advertising and popular culture into their work in the late 1950s. The Dwan Gallery exhibition, My Country ‘Tis of Thee, includes Rosenquist’s Hey! Let’s Go for a Ride (1961) and also features other young artists such as Indiana, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann.

In December the Museum of Modern Art, New York, hosts the Symposium on Pop Art, moderated by Peter Selz, Curator of Painting and Sculpture. The panel of speakers includes art historian and critic Dore Ashton; Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Henry Geldzahler; critic and professor Hilton Kramer; critic and author Stanley Kunitz; and critic and professor Leo Steinberg.3 Both Rosenquist and Marcel Duchamp are in attendance at the symposium.

1963

Rosenquist continues to experiment with including objects and three-dimensional elements in many of the paintings he creates this year; incorporating wood (in Nomad), chairs (in Candidate and Director), and painted Mylar or plastic sheets (in Morning Sun and Nomad). He also begins experimenting with freestanding, multimedia constructions and neon, in works such as AD, Soap Box Tree (1963), Untitled (Catwalk) (1963), and Untitled (reconstructed as Tumbleweed; 1963–66). Rosenquist will eventually destroy AD, Soap Box Tree and Untitled (Catwalk), along with most of his other early constructions.

Rosenquist receives the Norman Wait Harris Bronze Medal and one-thousand-dollar prize for A Lot to Like at the 66th Annual American Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. In February, Rosenquist is among seventy prominent artists to donate paintings and sculptures to benefit the Foundation for the Contemporary Performance Arts. He donates the painting The Promenade of Merce Cunningham (1963). The works are featured in a weeklong exhibition at Allan Stone Gallery, New York, with all proceeds supporting FCPA grants to short-run, avant-garde performances of music, dance, and theater in New York. (Dancer and choreographer Cunningham is slated to receive a grant from the foundation to stage a dance performance downtown.)4

Rosenquist’s work is represented in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition Six Painters and the Object, curated by Lawrence Alloway and including works by Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. The works by Rosenquist exhibited are Zone (1960–61), 4-1949 Guys (1962), The Lines Were Deeply Etched on the Map of Her Face (1962), Mayfair (1962), and Untitled (Blue Sky) (1962). The show travels to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it is presented in conjunction with Six More, featuring six West Coast artists. In April, Shadows (1961), Halved Apricots (1962), and The Promenade of Merce Cunningham (1963) appear in Pop! Goes the Easel at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, curated by Douglas MacAgy. I Love You with My Ford (1961), Look Alive (Blue Feet, Look Alive) (1961), Tube (1962), and Morning Sun (1963) are included in The Popular Image Exhibition, a large-scale compendium of Pop and Fluxus art curated by Alice Denney, at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenquist’s painting Vestigial Appendage (1962) is included in the group exhibition De A à Z 1963: 31 peintres americains choisis par The Art Institute of Chicago, one of the first European exhibitions to include his work, presented at the Centre Culturel Américain, Paris.

Rosenquist is also one of fifteen painters and sculptors included in Dorothy Miller’s Americans 1963 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. On view are Rosenquist’s paintings The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961), Pushbutton (1961), Air Hammer (1962), Marilyn Monroe I (1962), Portrait of the Scull Family (1962), Waves (1962), 1, 2, 3, Outside (1963), and Above the Square (1963). His second solo exhibition is advertised by the Green Gallery, New York, in the spring, but is postponed until the following year, as several works for the exhibition are on loan to the Guggenheim Museum’s Six Painters and the Object and the Museum of Modern Art’s Americans 1963.

In June, Charles Henri Ford brings Rosenquist, Robert Indiana, and Andy Warhol to Joseph Cornell’s studio on Utopia Parkway in Queens, where they meet the artist.5 In September, Rosenquist’s work is represented by the painting The Space That Won’t Fail (1962) in Pop Art USA at the Oakland Museum, California, which includes work from both East and West Coast artists. In October, the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, presents The Popular Image, one of the first European overviews of American Pop art. Included is Rosenquist’s Rainbow (1962). Nomad (1963) is included in the fall exhibition Mixed Media and Pop Art at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo. The Albright-Knox acquires the painting, one of the first Rosenquist works to enter a museum collection. In the fall Rosenquist moves his studio from Coenties Slip to the third floor of 429 Broome Street.

Americans 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1963. Rosenquist’s parents, Ruth and Louis, in front of Marilyn Monroe I, 1962, and Above the Square, 1963.

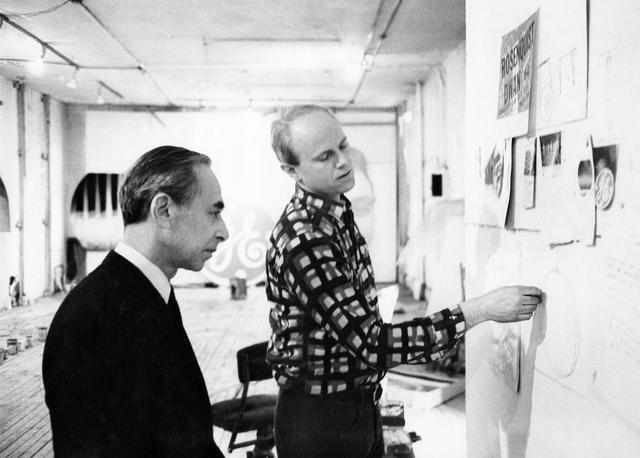

Dick Bellamy and James Rosenquist standing in front of Untitled (Two Chairs) (1963) at the opening of James Rosenquist, Green Gallery, 1964.

1964

Rosenquist’s work is represented in Four Environments by Four New Realists at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, by the works Capillary Action II (1963), Doorstop (1963), and Untitled (Catwalk) (1963). Green Gallery, New York, hosts the second solo exhibition of his work. Works shown include AD, Soap Box Tree (1963, destroyed), Binoculars (1963, destroyed), Candidate (1963; repainted as Silo, 1963–64), Capillary Action (1963), Early in the Morning (1963), He Swallowed the Chain (1963), Nomad (1963), 1, 2, 3, Outside (1963), Untitled (Two Chairs) (1963), and Untitled (1963; reworked as Tumbleweed, 1963–66). The opening is filmed and Rosenquist’s dealer, Richard Bellamy, as well as Sidney Janis and collector Robert Scull are interviewed about Pop art for a half-hour news segment, “Art for Whose Sake?” to be broadcast during the Eye on New York program on WCBS Channel 2 on March 17 and 21. In February, Gene Swenson’s “What Is Pop Art? Part II: Stephen Durkee, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, Tom Wesselmann,” which includes an interview with Rosenquist, is published in Art News.

In the spring Rosenquist’s work is featured in the Amerikansk pop-konst exhibition organized by the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. He travels to Europe for the first time, crossing the Atlantic by boat, for the opening of his solo show at Galerie Ileana Sonnabend in Paris and the Venice Biennale, both of which begin in June. André Breton, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, and Barnett Newman, along with his wife Annalee, attend the Sonnabend opening. In Paris, Rosenquist visits the Louvre. During his stay in Italy,

he meets artist Mimmo Rotella.

In September, Rosenquist’s son, John, is born in New York. Rosenquist serves as a visiting art lecturer at Yale University, New Haven, during the first semester of the 1964–65 school year at the invitation of Jack Tworkov. In the fall he travels to Los Angeles for the opening of his solo show at the Dwan Gallery, and is also featured in a solo show in Turin, Italy, at the Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone. Commissioned by architect Philip Johnson, Rosenquist’s World’s Fair Mural (1963–64), a twenty-by-twenty-foot oil painting on Masonite, is featured on the Theaterama building at the

New York State Pavilion of the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair. Rosenquist becomes affiliated with the Leo Castelli Gallery.

Rosenquist gathers photographs and information about the F-111 fighter bomber being developed for the United States military, and begins painting F-111 (1964–65), which will measure ten by eighty-six feet when complete. With word spreading about the monumental painting, a succession of artists and members of the art world visit the Broome Street studio, where Rosenquist documents them in a series of Polaroid photographs. At the suggestion of Jasper Johns, Rosenquist begins working with Tatyana Grosman at Universal Limited Art Editions—a printmaking workshop located at Grosman’s home in West Islip, Long Island. Between 1964 and 1966, he produces seven lithographs at ULAE, including Spaghetti and Grass (1964–65), Campaign (1965), and Circles of Confusion I (1965). Rosenquist continues to work with ULAE over the course of the next forty years.

1965

Rosenquist is one of five artists (the others are Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann) featured in lavish studio pictorials in one of the first major books on the movement, Pop Art, with text by John Rublowsky and photographs by Ken Heyman. He is also included (along with the four artists in Rublowsky’s Pop Art and Jasper Johns) in Dorothy Herzka’s Pop Art One, a small-format portfolio of reproductions issued by the Publishing Institute of American Art. This portfolio includes Rosenquist’s Silver Skies (1962), Dishes (1964), Lanai (1964), and Untitled (Joan Crawford Says . . .) (1964). In the spring the painting F-111 (1964–65) is featured in the exhibition Rosenquist at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York. The work is installed along the four walls of the gallery’s front room. Rosenquist intends to sell the fifty-one panels of F-111 separately. The day after the exhibition closes, however, Robert Scull buys the entire work. The purchase is featured in an article in The New York Times, in which Scull is quoted: “We would consider loaning it to institutions because it is the most important statement made in art in the last fifty years.”6

In the summer Rosenquist studies Eastern philosophy and history at the Institute of Humanist Studies in Aspen, Colorado, where he is an artist-in-residence along with Allan D’Arcangelo, Friedel Dzubas, and Larry Poons. He meets artist Marcel Duchamp at the New York home of Yvonne Thomas. F-111 is exhibited at the Jewish Museum, New York, in Rosenquist’s first solo museum exhibition. He is awarded the Premio Internacional de Pintura at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires, for Painting for the American Negro (1962–63). In September he travels to Stockholm for the exhibition James Rosenquist: F-111 at the Moderna Museet, and from there flies to Leningrad, where he meets Evgeny Rukhin, a Russian artist with whom he has been corresponding. James Rosenquist: F-111 will tour to major venues across Europe over the course of the next year. In the fall the Green Gallery closes.

Three of Rosenquist’s multicolor screenprints are included in Rosa Esman’s portfolio 11 Pop Artists, published by Original Editions. One of the screenprints, Whipped Butter for Eugen Ruchin (1965), is dedicated to Rukhin. The planes of distinct, flat blue, yellow, and red within this work are reminiscent of Soviet propaganda posters of the 1930s.

Leo Castelli and Rosenquist, Broome Street studio, New York, 1966. Works partially visible in background, left to right: Waco, Texas; Circles of Confusion and Lite Bulb in progress; and Big Bo; all 1966

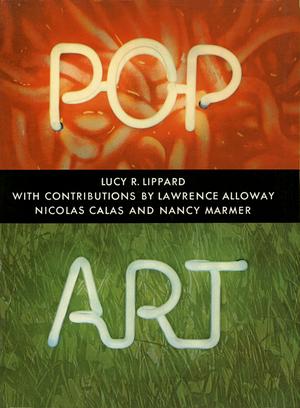

Cover design by Rosenquist for first edition of Lucy Lippard's Pop Art (1966)

1966

Rosenquist commissions the fashion designer Horst to tailor a brown-paper suit with paper donated by the Kleenex Company. He wears the suit to gallery and museum openings throughout the year, which attracts media attention, generating, among other pieces, an interview by Doon Arbus in New York magazine.7 Rosenquist contributes a twenty-four-by-twenty-four-inch panel to the Peace Tower (“The Artists’ Tower of Protest”) that is dedicated on February 26 in protest against the Vietnam War. The tower, organized by artists Mark di Suvero and Irving Petlin, is a fifty-eight-foot-tall structure covered with artwork contributed by over four hundred artists that is installed on an empty lot on Sunset Avenue in Hollywood, California, and remains on view for three months.8 When the lease on the site expires and is not renewed, the tower is dismantled and the panels sold in a fund-raising effort by the Los Angeles Peace Center to raise money for the cause.9 Rosenquist participates in a panel discussion, “What about Pop Art?,” with critic Gene Swenson and media theorist Marshall McLuhan at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. He is commissioned by Playboy magazine to create a painting that “transforms the idea of the Playmate into fine art.”10 Larry Rivers, George Segal, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, and other

artists are also asked to participate. In response Rosenquist paints Playmate, which he identifies as a pregnant playmate suffering from food cravings. This work will be reproduced in an article in the January 1967 issue of Playboy. In October, Rosenquist travels to Japan for the Two Decades of American Painting exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and hosted by the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. He wears the brown-paper suit to the opening. He then tours Japan for a month, before traveling to Alaska, France, and Sweden. In November the first edition of the major contemporary monograph Pop Art by Lucy Lippard is published. Its cover design, by Rosenquist, features the title of the book in neon tubes overlaying an image of his lithograph Spaghetti and Grass (1964–65).

1967

In March, Rosenquist moves his family’s primary residence from Manhattan to East Hampton, New York, where he also builds a studio. In it he installs a Griffin lithography press custom made by Reynaldo Terrazas. Rosenquist retains his studio on Broome Street. He makes and contributes a nine-by-twenty-four-foot painting, Fruit Salad on an Ensign’s Chest, to the Spring Mobilization against the War in Vietnam rally in New York, in which several thousand demonstrators march from Central Park to the United Nations. The painting’s imagery features a woman’s hand shaking salt from a saltshaker onto a field of combat medals, known in military parlance as “fruit salad.” The painting—positioned atop a flatbed truck, which also carries poets who are reading aloud from their work—is destroyed during the procession. Rosenquist’s thirty-three-by-seventeen-foot painting Fire Slide (1967) is installed in the United States Pavilion—a geodesic dome designed by R. Buckminster Fuller—at Expo 67, the Montreal World’s Fair.11 Rosenquist’s installation Forest Ranger (1967) is presented at Palazzo Grassi, Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume, Venice, in the exhibition Campo Vitale: Mostra intemazionale d’arte contemporanea. The Mylar paintings in this installation—which includes a work with the same title created the previous year—are cut into vertical strips that hang like banners from the ceiling. The artist intends the viewers to walk through their openings. A condensed version of F-111 (1964–65) is included in Environment U.S.A.: 1957–1967, the American component of the ninth São Paulo Biennial exhibition in Brazil. In November he creates a large-scale installation work of aluminum foil and neon tubing, which hangs from the ceiling of the field house at Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois. (Rosenquist makes at least two additional versions of this work, one of which is constructed and installed this year in Robert Rauschenberg’s studio space in a former chapel on Lafayette Street in Manhattan.) The Peoria installation also includes a film program by the experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Rosenquist himself experiments with a number of film projects, which he abandons before completion. He is among sixteen artists featured in the oversized book of photographs by Italian Ugo Mulas New York: The New Art Scene, with text by Alan Solomon, Director of the Jewish Museum, New York. In December, Rosenquist’s painting Marilyn Monroe I (1962) is included in the exhibition Homage to Marilyn Monroe at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York.

Environment U.S.A.: 1957-1967, São Paulo Bienal, 1967. F-111 (1964-65) is partially visible in background at left.

James Rosenquist (in paper suit), Mary Lou Rosenquist, Jane and Brydon Smith interact with Rosenquist's Stellar Structure (1966) at the opening of James Rosenquist, National Gallery of Art, Ottawa, Canada, 1968

1968

Organized by curator Brydon Smith, Rosenquist’s first retrospective, with thirty-two works, opens at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in January. The National Gallery of Art acquires two Rosenquist paintings at this time: Painting for the American Negro (1962–63) and Capillary Action II (1963). F-111 (1964–65) is featured in the exhibition History Painting: Various Aspects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. F-111 is exhibited alongside three paintings from the museum’s permanent collection: The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David, The Rape of the Sabine Women (ca. 1633–34) by Nicolas Poussin, and Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emanuel Leutze.12 Henry Geldzahler, Curator of Contemporary Art, writes an essay in defense of the installation of F-111 at the museum in the March issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, in the face of mounting criticism. Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, presents a solo exhibition featuring Rosenquist’s Forest Ranger installation. The artist travels to France for the opening, returning to the United States after the outbreak of student protests in Paris. Rosenquist’s work is represented in documenta 4 in Kassel, West Germany, beginning in June. In November, Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone in Turin presents a solo show that includes several paintings on Mylar.

1969

Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, presents a solo exhibition featuring Rosenquist’s Horse Blinders (1968), a room-sized installation that fills the walls of the front gallery space. His work is presented in the Smithsonian Institution’s The Disappearance and Reappearance of the Image: Painting in the United States since 1945, which opens at the Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, and travels to Prague, Brussels, and three Romanian cities. Rosenquist’s work is also included in Henry Geldzahler’s exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. As a participant in the Art and Technology Program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Rosenquist visits American companies and manufacturing plants, including Container Corporation of America, Ampex, and RCA.13 He decides against creating a work of art for the program and instead considers the merits of an “invisible sculpture.”14

Rolf Rick, his wide, and Rosenquist in front of Area Code, 1970, in progress, East Hampton studio, New York, 1970