1933–50

James Albert Rosenquist is born on November 29, 1933, in Grand Forks, North Dakota, to Ruth Hendrickson Rosenquist and Louis Rosenquist, who are of Norwegian and Swedish descent respectively.

During Rosenquist’s childhood, his family moves from one Midwestern city or farming community to another, including Atwater, Perham, and Minneapolis in Minnesota, and Tipp City and Vandalia in Ohio. Rosenquist’s father works at a series of jobs, including a motor-court and gas-station operator, airplane mechanic, and other positions in the aviation industry. Rosenquist’s mother and his paternal uncle, Albert, have experience as pilots. By age eight Rosenquist has become an avid maker of model airplanes. In 1941 he visits the Minneapolis Institute of Arts with his mother, an amateur painter. When he shows an aptitude for sketching at an early age, she encourages him.

By 1944 his family has settled down in Minneapolis, purchasing a house on Nokomis Avenue. In his teenage years Rosenquist paints portraits and landscapes. He submits a painting of a sunset and wins a scholarship in junior high school for four Saturdays of art classes at the Minneapolis School of Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. At the institute Rosenquist is first exposed to quality art supplies—such as Arches and Strathmore papers, which he will use throughout his career—and takes classes with older students and teachers who have studied in Paris and across Europe on the GI Bill.

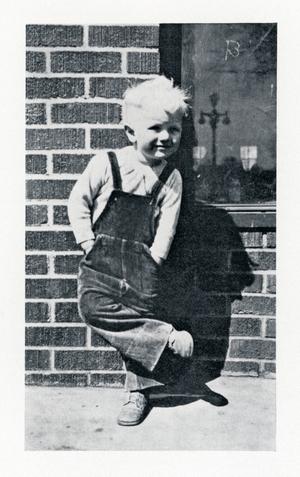

Rosenquist as a child, ca. 1938.

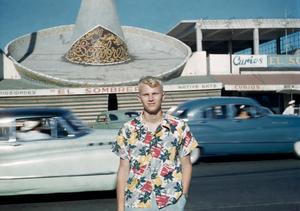

Rosenquist in Tijuana, where he drove with his father in 1951.

1951–54

In 1951 Rosenquist and his father travel by car to visit California and the Pacific Northwest. While in Southern California, they cross the border into Mexico. In spring 1952 Rosenquist graduates from Roosevelt High School in Minneapolis. With the encouragement of his mother, he enrolls in art classes at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He attends the university from fall 1952 until spring 1954, learning oil painting, egg tempera, and Renaissance underpainting from painter Cameron Booth.1 Booth—who had studied with the painter Hans Hofmann and taught at the Art Students League, New York, in the mid-1940s—becomes Rosenquist’s mentor. Booth takes Rosenquist and another student to view Impressionist and old master paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago.

During the summer of 1953, Rosenquist works for the commercial painting contractor W. G. Fischer. He travels across the Midwest as part of a Fischer crew, painting Phillips 66 signs, gasoline and storage tanks, refinery equipment, and grain elevators. After leaving the University of Minnesota with an associate’s degree in studio art, Rosenquist paints billboards in Minneapolis and Saint Paul for General Outdoor Advertising, including promotional signs for the movie Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, advertisements in Saint Louis for Corby’s Whiskey, and advertisements in Minneapolis for Northwest Airlines and Coca-Cola. He travels to Florida and Cuba.

1955

Encouraged by Cameron Booth, Rosenquist applies to the Art Students League, New York. He receives a scholarship, which includes a year’s tuition but nothing for room and board. Rosenquist arrives in New York with a few hundred dollars as well as Booth’s letter of introduction and his list of affordable restaurants. At the Art Students League, Rosenquist studies under Will Barnet, Edwin Dickinson, Sydney E. Dickinson, George Grosz, Robert Beverly Hale, Morris Kantor, and Vaclav Vytlacil. Rosenquist frequents the Cedar Tavern, where he meets painters Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Milton Resnick. Diagnosed with pneumonia before the end of the academic year, Rosenquist is treated in the welfare ward at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan.

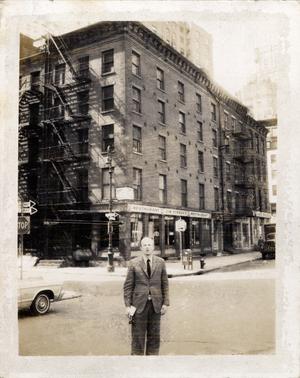

James Rosenquist during the 1955–56 academic year at the Art Students League, New York.

Rosenquist doing a headstand in Roland and Joyce Stearns’s Lincoln Premier Convertible, Westchester County, New York, 1956.

1956

Rosenquist leaves the Art Students League, New York, after the 1955–56 academic year. He works as a chauffeur and bartender for Roland and Joyce Stearns and also minds their children at the family’s Irvington, New York, estate. There he works on small abstract oils and drawings in an octagonal studio space on the top floor of the Stearns home. In September he meets artists Jasper Johns, Ray Johnson, and Robert Rauschenberg in New York. He also meets Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jack Youngerman this year.

1957

Rosenquist quits his job with the Stearns family and moves back to Manhattan. He lives for a time in a loft at Sixty-third Street and Amsterdam Avenue, which he shares with Takeshi Asada, Alice Forman, Chuck Hinman, Peggy Smith, and Joan Warner. Rosenquist joins Local 230 of the International Brotherhood of Painters and Allied Trades union and begins painting billboards in New York. His first assignment is to paint a Hebrew National Salami sign on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn for A. H. Villepigue Company. The firm lets him go shortly after this task. He then paints signs in Brooklyn for General Outdoor Advertising but is subsequently laid off. Rosenquist travels home to Minnesota, retaining his studio in New York. In Minneapolis he paints promotional signs on a freelance basis, including a number of automobile advertisements on building exteriors. He subsequently returns to New York, where he begins painting billboards for Artkraft Strauss Sign Corporation. He lives briefly in a studio at Broadway and Twenty-seventh Street. In his spare time Rosenquist attends drawing classes with Claes Oldenburg and Henry Pearson. The sessions are organized by Robert Indiana and Jack Youngerman, whose wife, Delphine Seyrig, serves as a model. Simultaneously, Rosenquist creates abstract pieces, including a nine-by-seventeen-foot drawing, anticipating the large scale of his future art.2

Cadillac Rosenquist painted on the outside of an auto shop, Minneapolis, 1958.

The completed Fugitive Kind billboard, Artkraft Strauss, the block-long Astor and Victoria sign, Times Square, Broadway between Forty-fifth and Forty-sixth Streets, New York, ca. 1960 (movie release April 14, 1960; photograph processing date April 1960).

1958

As a commercial artist, Rosenquist paints billboards in Manhattan and Brooklyn, including signs in Times Square for the Astor Theatre, Victoria Theater, and Morosco Theatre, all located at Broadway and Forty-fifth Street. He moves to an apartment and studio at Second Avenue and Ninety-fourth Street, where he continues to create abstract paintings and works on paper. He also begins looking for a separate studio space. In the spring Rosenquist’s abstract painting Passing before the Horizon (1957) is included in the 1958 Biennial: Paintings, Prints, Sculpture at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

1959

At age twenty-five Rosenquist becomes head painter at Artkraft Strauss Sign Corporation. He meets Gene Moore, head window designer at Tiffany & Co., Bonwit Teller, and other stores, who hires him periodically over the next two years to design displays and paint backdrops for store windows on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Bonwit Teller window display with Rosenquist’s “Statue of Liberty” painted backdrop, 1961.

Rosenquist outside his studio at 3–5 Coenties Slip (third-floor corner), New York, 1960.

1960

In June, Rosenquist marries textile designer Mary Lou Adams, whom he had met while painting Times Square billboards. He is featured in the United Press International article “Billboard Painter, Local 230, Is Broadway’s Biggest Painter.” Ray Johnson introduces him to painters Agnes Martin and Lenore Tawney, who live and work in Lower Manhattan. Rosenquist quits working for Artkraft Strauss Sign Corporation after two fellow painters fall from scaffolding and die. He rents the studio that had been Martin’s at 3–5 Coenties Slip, near the workspaces of Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jack Youngerman, and commits himself to a career in fine art. He shares his studio space with Charles Hinman for part of the year. At Coenties Slip, Rosenquist begins creating paintings, such as Zone (1960–61), that incorporate commercial sign-painting techniques as well as images of people and products derived from advertisements and photographs. With the financial backing of Robert and Ethel Scull, Richard Bellamy—who

will become Rosenquist’s first dealer—opens the Green Gallery in New York in October with the exhibition Mark di Suvero.

1961

Several art dealers pay visits to Rosenquist’s Coenties Slip studio, including Richard Bellamy, Leo Castelli with his gallery manager Ivan Karp, Ileana Sonnabend, and Allan Stone. Henry Geldzahler, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and several private collectors also come. Stone offers Rosenquist an exhibition with Robert Indiana, which both artists turn down. Rosenquist makes his first sale with Robert Scull’s purchase of The Light That Won’t Fail II (1961). Scull is president and owner of a large fleet of New York taxicabs: Super Operating Corporation. He will become one of the largest private collectors of 1960s Pop art and a Rosenquist enthusiast. In October a photograph of Rosenquist painting The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961) appears on the cover of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Sunday Pictures magazine. Rosenquist meets critic Gene Swenson, whose sympathetic interviews with him and others associated with Pop art will help legitimize their work within the art world.

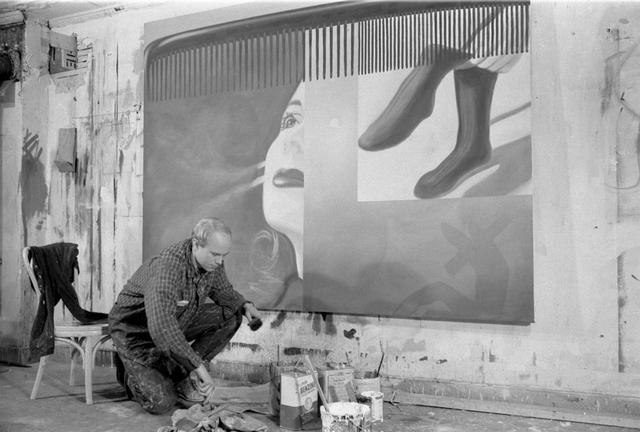

Rosenquist working on The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961), Coenties Slip studio, New York, 1961. Photo by Paul Berg.

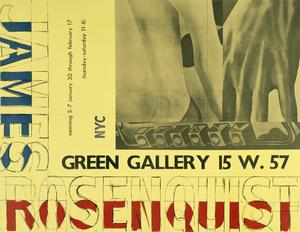

Poster designed by Rosenquist showing Pushbutton, 1961, for his exhibition at Green Gallery, New York, January 30 – February 17, 1962.

1962

In many works painted this year, such as Untitled (Two Chairs), Capillary Action, and Untitled (Blue Sky), Rosenquist attaches small rectangular or circular canvases to the surface of the larger paintings. He produces his first print, Certificate, a small photoengraving and etching for inclusion in the fifth volume of Italian gallerist Arturo Schwarz’s portfolio International Anthology of Contemporary Engraving: The International Avant-garde: America Discovered. Billy Kluver selects the works for the portfolio.

The Green Gallery, New York, presents Rosenquist’s first solo show, opening in January, for which the artist designs a poster featuring his painting Pushbutton (1961). The exhibition, organized by Richard Bellamy, sells out. Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, an early collector of Pop art, purchases three paintings: Pushbutton, Air Hammer (1962), and Waves (1962). In March, Art International publishes Max Kozloff’s “‘Pop’ Culture, Metaphysical Disgust, and the New Vulgarians,” one of the first articles linking Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Rosenquist together as a group. In April, Rosenquist’s Shadows (1961) is included alongside works by Dine, Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, and Robert Rauschenberg in the exhibition 1961 organized by Douglas MacAgy at the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts. In September, Gene Swenson’s article “The New American Sign Painters” is published in Art News, which associates Rosenquist with Dine, Robert Indiana, Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. In the fall Rosenquist’s work is included in Art 1963: A New Vocabulary, organized by Billy Kluver for the Fine Arts Committee of the Philadelphia YM/YWHA Arts Council; other artists represented include Dine, Johns, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, George Segal, and Jean Tinguely. Instrumental in recognizing the significance of the young artists who will be identified as “Pop artists,” Kluver, a scientist at Bell Labs, will organize several early exhibitions featuring their work. Rosenquist’s work is represented in seminal exhibitions at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York and the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. The title of the exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, International Exhibition of the New Realists, galvanizes the name “New Realists” for the American and British artists, who are represented alongside the work of the continental Europeans known as the Nouveaux Realistes. “New Realism” would shortly be replaced by “Pop art,” a term critic Lawrence Alloway had used to identify the work of several British artists who incorporated the imagery of advertising and popular culture into their work in the late 1950s. The Dwan Gallery exhibition, My Country ‘Tis of Thee, includes Rosenquist’s Hey! Let’s Go for a Ride (1961) and also features other young artists such as Indiana, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann.

In December the Museum of Modern Art, New York, hosts the Symposium on Pop Art, moderated by Peter Selz, Curator of Painting and Sculpture. The panel of speakers includes art historian and critic Dore Ashton; Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Henry Geldzahler; critic and professor Hilton Kramer; critic and author Stanley Kunitz; and critic and professor Leo Steinberg.3 Both Rosenquist and Marcel Duchamp are in attendance at the symposium.

1963

Rosenquist continues to experiment with including objects and three-dimensional elements in many of the paintings he creates this year; incorporating wood (in Nomad), chairs (in Candidate and Director), and painted Mylar or plastic sheets (in Morning Sun and Nomad). He also begins experimenting with freestanding, multimedia constructions and neon, in works such as AD, Soap Box Tree (1963), Untitled (Catwalk) (1963), and Untitled (reconstructed as Tumbleweed; 1963–66). Rosenquist will eventually destroy AD, Soap Box Tree and Untitled (Catwalk), along with most of his other early constructions.

Rosenquist receives the Norman Wait Harris Bronze Medal and one-thousand-dollar prize for A Lot to Like at the 66th Annual American Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. In February, Rosenquist is among seventy prominent artists to donate paintings and sculptures to benefit the Foundation for the Contemporary Performance Arts. He donates the painting The Promenade of Merce Cunningham (1963). The works are featured in a weeklong exhibition at Allan Stone Gallery, New York, with all proceeds supporting FCPA grants to short-run, avant-garde performances of music, dance, and theater in New York. (Dancer and choreographer Cunningham is slated to receive a grant from the foundation to stage a dance performance downtown.)4

Rosenquist’s work is represented in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition Six Painters and the Object, curated by Lawrence Alloway and including works by Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. The works by Rosenquist exhibited are Zone (1960–61), 4-1949 Guys (1962), The Lines Were Deeply Etched on the Map of Her Face (1962), Mayfair (1962), and Untitled (Blue Sky) (1962). The show travels to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it is presented in conjunction with Six More, featuring six West Coast artists. In April, Shadows (1961), Halved Apricots (1962), and The Promenade of Merce Cunningham (1963) appear in Pop! Goes the Easel at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, curated by Douglas MacAgy. I Love You with My Ford (1961), Look Alive (Blue Feet, Look Alive) (1961), Tube (1962), and Morning Sun (1963) are included in The Popular Image Exhibition, a large-scale compendium of Pop and Fluxus art curated by Alice Denney, at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenquist’s painting Vestigial Appendage (1962) is included in the group exhibition De A à Z 1963: 31 peintres americains choisis par The Art Institute of Chicago, one of the first European exhibitions to include his work, presented at the Centre Culturel Américain, Paris.

Rosenquist is also one of fifteen painters and sculptors included in Dorothy Miller’s Americans 1963 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. On view are Rosenquist’s paintings The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961), Pushbutton (1961), Air Hammer (1962), Marilyn Monroe I (1962), Portrait of the Scull Family (1962), Waves (1962), 1, 2, 3, Outside (1963), and Above the Square (1963). His second solo exhibition is advertised by the Green Gallery, New York, in the spring, but is postponed until the following year, as several works for the exhibition are on loan to the Guggenheim Museum’s Six Painters and the Object and the Museum of Modern Art’s Americans 1963.

In June, Charles Henri Ford brings Rosenquist, Robert Indiana, and Andy Warhol to Joseph Cornell’s studio on Utopia Parkway in Queens, where they meet the artist.5 In September, Rosenquist’s work is represented by the painting The Space That Won’t Fail (1962) in Pop Art USA at the Oakland Museum, California, which includes work from both East and West Coast artists. In October, the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, presents The Popular Image, one of the first European overviews of American Pop art. Included is Rosenquist’s Rainbow (1962). Nomad (1963) is included in the fall exhibition Mixed Media and Pop Art at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo. The Albright-Knox acquires the painting, one of the first Rosenquist works to enter a museum collection. In the fall Rosenquist moves his studio from Coenties Slip to the third floor of 429 Broome Street.

Americans 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1963. Rosenquist’s parents, Ruth and Louis, in front of Marilyn Monroe I, 1962, and Above the Square, 1963.

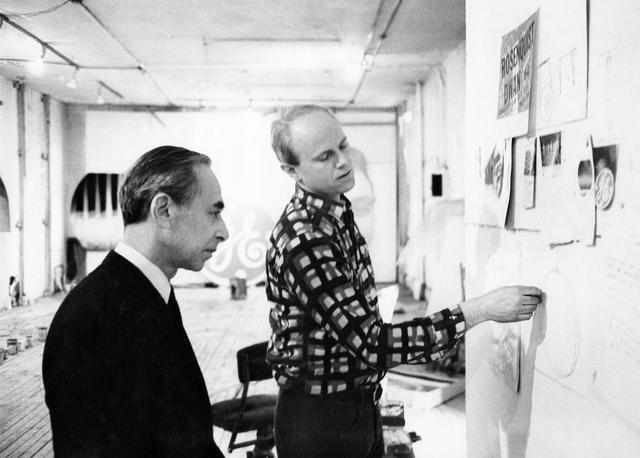

Dick Bellamy and James Rosenquist standing in front of Untitled (Two Chairs) (1963) at the opening of James Rosenquist, Green Gallery, 1964.

1964

Rosenquist’s work is represented in Four Environments by Four New Realists at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, by the works Capillary Action II (1963), Doorstop (1963), and Untitled (Catwalk) (1963). Green Gallery, New York, hosts the second solo exhibition of his work. Works shown include AD, Soap Box Tree (1963, destroyed), Binoculars (1963, destroyed), Candidate (1963; repainted as Silo, 1963–64), Capillary Action (1963), Early in the Morning (1963), He Swallowed the Chain (1963), Nomad (1963), 1, 2, 3, Outside (1963), Untitled (Two Chairs) (1963), and Untitled (1963; reworked as Tumbleweed, 1963–66). The opening is filmed and Rosenquist’s dealer, Richard Bellamy, as well as Sidney Janis and collector Robert Scull are interviewed about Pop art for a half-hour news segment, “Art for Whose Sake?” to be broadcast during the Eye on New York program on WCBS Channel 2 on March 17 and 21. In February, Gene Swenson’s “What Is Pop Art? Part II: Stephen Durkee, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, Tom Wesselmann,” which includes an interview with Rosenquist, is published in Art News.

In the spring Rosenquist’s work is featured in the Amerikansk pop-konst exhibition organized by the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. He travels to Europe for the first time, crossing the Atlantic by boat, for the opening of his solo show at Galerie Ileana Sonnabend in Paris and the Venice Biennale, both of which begin in June. André Breton, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, and Barnett Newman, along with his wife Annalee, attend the Sonnabend opening. In Paris, Rosenquist visits the Louvre. During his stay in Italy,

he meets artist Mimmo Rotella.

In September, Rosenquist’s son, John, is born in New York. Rosenquist serves as a visiting art lecturer at Yale University, New Haven, during the first semester of the 1964–65 school year at the invitation of Jack Tworkov. In the fall he travels to Los Angeles for the opening of his solo show at the Dwan Gallery, and is also featured in a solo show in Turin, Italy, at the Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone. Commissioned by architect Philip Johnson, Rosenquist’s World’s Fair Mural (1963–64), a twenty-by-twenty-foot oil painting on Masonite, is featured on the Theaterama building at the

New York State Pavilion of the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair. Rosenquist becomes affiliated with the Leo Castelli Gallery.

Rosenquist gathers photographs and information about the F-111 fighter bomber being developed for the United States military, and begins painting F-111 (1964–65), which will measure ten by eighty-six feet when complete. With word spreading about the monumental painting, a succession of artists and members of the art world visit the Broome Street studio, where Rosenquist documents them in a series of Polaroid photographs. At the suggestion of Jasper Johns, Rosenquist begins working with Tatyana Grosman at Universal Limited Art Editions—a printmaking workshop located at Grosman’s home in West Islip, Long Island. Between 1964 and 1966, he produces seven lithographs at ULAE, including Spaghetti and Grass (1964–65), Campaign (1965), and Circles of Confusion I (1965). Rosenquist continues to work with ULAE over the course of the next forty years.

1965

Rosenquist is one of five artists (the others are Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann) featured in lavish studio pictorials in one of the first major books on the movement, Pop Art, with text by John Rublowsky and photographs by Ken Heyman. He is also included (along with the four artists in Rublowsky’s Pop Art and Jasper Johns) in Dorothy Herzka’s Pop Art One, a small-format portfolio of reproductions issued by the Publishing Institute of American Art. This portfolio includes Rosenquist’s Silver Skies (1962), Dishes (1964), Lanai (1964), and Untitled (Joan Crawford Says . . .) (1964). In the spring the painting F-111 (1964–65) is featured in the exhibition Rosenquist at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York. The work is installed along the four walls of the gallery’s front room. Rosenquist intends to sell the fifty-one panels of F-111 separately. The day after the exhibition closes, however, Robert Scull buys the entire work. The purchase is featured in an article in The New York Times, in which Scull is quoted: “We would consider loaning it to institutions because it is the most important statement made in art in the last fifty years.”6

In the summer Rosenquist studies Eastern philosophy and history at the Institute of Humanist Studies in Aspen, Colorado, where he is an artist-in-residence along with Allan D’Arcangelo, Friedel Dzubas, and Larry Poons. He meets artist Marcel Duchamp at the New York home of Yvonne Thomas. F-111 is exhibited at the Jewish Museum, New York, in Rosenquist’s first solo museum exhibition. He is awarded the Premio Internacional de Pintura at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires, for Painting for the American Negro (1962–63). In September he travels to Stockholm for the exhibition James Rosenquist: F-111 at the Moderna Museet, and from there flies to Leningrad, where he meets Evgeny Rukhin, a Russian artist with whom he has been corresponding. James Rosenquist: F-111 will tour to major venues across Europe over the course of the next year. In the fall the Green Gallery closes.

Three of Rosenquist’s multicolor screenprints are included in Rosa Esman’s portfolio 11 Pop Artists, published by Original Editions. One of the screenprints, Whipped Butter for Eugen Ruchin (1965), is dedicated to Rukhin. The planes of distinct, flat blue, yellow, and red within this work are reminiscent of Soviet propaganda posters of the 1930s.

Leo Castelli and Rosenquist, Broome Street studio, New York, 1966. Works partially visible in background, left to right: Waco, Texas; Circles of Confusion and Lite Bulb in progress; and Big Bo; all 1966

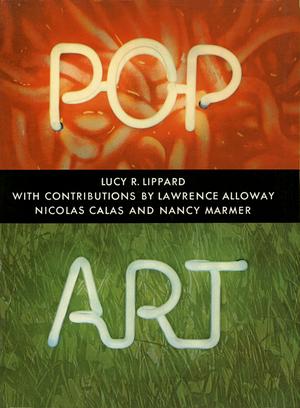

Cover design by Rosenquist for first edition of Lucy Lippard's Pop Art (1966)

1966

Rosenquist commissions the fashion designer Horst to tailor a brown-paper suit with paper donated by the Kleenex Company. He wears the suit to gallery and museum openings throughout the year, which attracts media attention, generating, among other pieces, an interview by Doon Arbus in New York magazine.7 Rosenquist contributes a twenty-four-by-twenty-four-inch panel to the Peace Tower (“The Artists’ Tower of Protest”) that is dedicated on February 26 in protest against the Vietnam War. The tower, organized by artists Mark di Suvero and Irving Petlin, is a fifty-eight-foot-tall structure covered with artwork contributed by over four hundred artists that is installed on an empty lot on Sunset Avenue in Hollywood, California, and remains on view for three months.8 When the lease on the site expires and is not renewed, the tower is dismantled and the panels sold in a fund-raising effort by the Los Angeles Peace Center to raise money for the cause.9 Rosenquist participates in a panel discussion, “What about Pop Art?,” with critic Gene Swenson and media theorist Marshall McLuhan at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. He is commissioned by Playboy magazine to create a painting that “transforms the idea of the Playmate into fine art.”10 Larry Rivers, George Segal, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, and other

artists are also asked to participate. In response Rosenquist paints Playmate, which he identifies as a pregnant playmate suffering from food cravings. This work will be reproduced in an article in the January 1967 issue of Playboy. In October, Rosenquist travels to Japan for the Two Decades of American Painting exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and hosted by the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. He wears the brown-paper suit to the opening. He then tours Japan for a month, before traveling to Alaska, France, and Sweden. In November the first edition of the major contemporary monograph Pop Art by Lucy Lippard is published. Its cover design, by Rosenquist, features the title of the book in neon tubes overlaying an image of his lithograph Spaghetti and Grass (1964–65).

1967

In March, Rosenquist moves his family’s primary residence from Manhattan to East Hampton, New York, where he also builds a studio. In it he installs a Griffin lithography press custom made by Reynaldo Terrazas. Rosenquist retains his studio on Broome Street. He makes and contributes a nine-by-twenty-four-foot painting, Fruit Salad on an Ensign’s Chest, to the Spring Mobilization against the War in Vietnam rally in New York, in which several thousand demonstrators march from Central Park to the United Nations. The painting’s imagery features a woman’s hand shaking salt from a saltshaker onto a field of combat medals, known in military parlance as “fruit salad.” The painting—positioned atop a flatbed truck, which also carries poets who are reading aloud from their work—is destroyed during the procession. Rosenquist’s thirty-three-by-seventeen-foot painting Fire Slide (1967) is installed in the United States Pavilion—a geodesic dome designed by R. Buckminster Fuller—at Expo 67, the Montreal World’s Fair.11 Rosenquist’s installation Forest Ranger (1967) is presented at Palazzo Grassi, Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume, Venice, in the exhibition Campo Vitale: Mostra intemazionale d’arte contemporanea. The Mylar paintings in this installation—which includes a work with the same title created the previous year—are cut into vertical strips that hang like banners from the ceiling. The artist intends the viewers to walk through their openings. A condensed version of F-111 (1964–65) is included in Environment U.S.A.: 1957–1967, the American component of the ninth São Paulo Biennial exhibition in Brazil. In November he creates a large-scale installation work of aluminum foil and neon tubing, which hangs from the ceiling of the field house at Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois. (Rosenquist makes at least two additional versions of this work, one of which is constructed and installed this year in Robert Rauschenberg’s studio space in a former chapel on Lafayette Street in Manhattan.) The Peoria installation also includes a film program by the experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Rosenquist himself experiments with a number of film projects, which he abandons before completion. He is among sixteen artists featured in the oversized book of photographs by Italian Ugo Mulas New York: The New Art Scene, with text by Alan Solomon, Director of the Jewish Museum, New York. In December, Rosenquist’s painting Marilyn Monroe I (1962) is included in the exhibition Homage to Marilyn Monroe at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York.

Environment U.S.A.: 1957-1967, São Paulo Bienal, 1967. F-111 (1964-65) is partially visible in background at left.

James Rosenquist (in paper suit), Mary Lou Rosenquist, Jane and Brydon Smith interact with Rosenquist's Stellar Structure (1966) at the opening of James Rosenquist, National Gallery of Art, Ottawa, Canada, 1968

1968

Organized by curator Brydon Smith, Rosenquist’s first retrospective, with thirty-two works, opens at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in January. The National Gallery of Art acquires two Rosenquist paintings at this time: Painting for the American Negro (1962–63) and Capillary Action II (1963). F-111 (1964–65) is featured in the exhibition History Painting: Various Aspects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. F-111 is exhibited alongside three paintings from the museum’s permanent collection: The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David, The Rape of the Sabine Women (ca. 1633–34) by Nicolas Poussin, and Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emanuel Leutze.12 Henry Geldzahler, Curator of Contemporary Art, writes an essay in defense of the installation of F-111 at the museum in the March issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, in the face of mounting criticism. Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, presents a solo exhibition featuring Rosenquist’s Forest Ranger installation. The artist travels to France for the opening, returning to the United States after the outbreak of student protests in Paris. Rosenquist’s work is represented in documenta 4 in Kassel, West Germany, beginning in June. In November, Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone in Turin presents a solo show that includes several paintings on Mylar.

1969

Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, presents a solo exhibition featuring Rosenquist’s Horse Blinders (1968), a room-sized installation that fills the walls of the front gallery space. His work is presented in the Smithsonian Institution’s The Disappearance and Reappearance of the Image: Painting in the United States since 1945, which opens at the Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, and travels to Prague, Brussels, and three Romanian cities. Rosenquist’s work is also included in Henry Geldzahler’s exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. As a participant in the Art and Technology Program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Rosenquist visits American companies and manufacturing plants, including Container Corporation of America, Ampex, and RCA.13 He decides against creating a work of art for the program and instead considers the merits of an “invisible sculpture.”14

Rolf Rick, his wide, and Rosenquist in front of Area Code, 1970, in progress, East Hampton studio, New York, 1970

1970

In the spring Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, presents Rosenquist’s recent room installation Horizon Home Sweet Home (1970). Like F-111 (1964–65) and Horse Blinders (1968), it is installed along the four walls of the gallery’s front room. The work contains no representational imagery. It comprises twenty-seven panels (twenty-one are colored, and six have reflective silver Mylar film loosely stretched over them) staggered along the walls of the gallery space, with dry-ice fog hovering along the floor.

The six panels with Mylar (a material also incorporated in Area Code [1970] and Flamingo Capsule [1970]) distort the reflections of the colored panels and the spectators in the room. Prior to the exhibition Rosenquist had developed and experimented with the Horizon Home Sweet Home installation in his Broome Street studio as well as in a loft space on Wooster Street owned by art dealer Richard Feigen. In the fall Castelli exhibits the paintings Area Code and Flamingo Capsule. Rosenquist travels to Germany in November with his wife for a solo show at Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne, featuring Slush Thrust (1970), another room installation. He is awarded the Friend of Japan Award from Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai (Japanese Society for International Cultural Relations), and designs a poster for the 1970 New York Film Festival.

1971

In February, Rosenquist, his wife, and their son are seriously injured in an automobile accident in Florida. While his wife and son convalesce in a Tampa hospital, Rosenquist travels back and forth between Tampa and New York, renting a two-story studio on Wall Street in Lower Manhattan. He begins collaborating with Donald Saff at Graphic studio/University of South Florida, Tampa, where he produces the print series Cold Light Suite (1971).

Rosenquist installing Horse Blinders (1968-69), Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne, 1972. Photo by Wolf P. Prange

1972

The Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, each host a Rosenquist retrospective this year. Evelyn Weiss organizes the retrospective James Rosenquist: Gemälde—Räume—Graphik for the German museum, which is installed at the Kunsthalle Köln. The Whitney presents the painting retrospective James Rosenquist, organized by Associate Curator Marcia Tucker, which travels to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. The Whitney show is negatively reviewed by John Canaday in The New York Times, who likens Rosenquist’s work to a corpse and the exhibition to a wake. In a letter to The New York Times, Rosenquist protests the critic’s choice of words in light of the 1971 accident that permanently injured his wife and son. “I know more about death than Mr. Canaday. I prefer life. Long live artists, long live art collectors, long live art dealers, long live art critics, but damn a person like Mr. Canaday,” he writes.15

Rosenquist demonstrates in Washington, D.C., against the Vietnam War, and is arrested and jailed for one night. He travels to London to work at Petersburg Press, where he produces several prints based on early paintings, such

as Hey! Let’s Go for a Ride (1961) and Pushbutton (1961). In New York he produces the four panels of the lithograph and screenprint Horse Blinders at Styria Studio with Marion Goodman, relating to the 1968 painting of the same name. Rosenquist will come to consider Horse Blinders to be his most important monumental print of the 1970s.16

1973

Rosenquist rents two storefronts, at 1724 and 1726 Seventh Avenue in Ybor City, Florida, to use as a studio. Founded at the end of the 1800s by Cuban immigrants, Ybor City is part of east Tampa. By 1973 he is also renting a studio on the Bowery in downtown Manhattan, as he continues to work in both Florida and New York. In the Bowery studio he returns to large-scale painting with such works as Paper Clip and produces experimental hanging works, one of which incorporates the Coca-Cola logo and is made from Tergal polyester fabric. The latter work hangs dipped into a trough of colored ink, which is gradually absorbed into the fabric through capillary action.17 Rosenquist’s work is represented in the exhibition Contemporanea in the fall at the Villa Borghese, Rome.

Rosenquist working on a series of drawings using an experimental technique of applying a blend of acrylic paint with a screenprint squeegee, Ybor City studio, Florida, 1974. Photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni

Artists' rights Senate subcommittee hearing, Washington, D.C., 1974. Left to right, seated: Congressman John Brademas, Congressman Edward Koch, Senator Jacob Javits, Marion Javits, and Senator Clairborne Pell; and standing: Rosenquist and Robert Rauschenberg

1974

Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition American Pop Art, curated by Lawrence Alloway, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. He completes the lithograph Off the Continental Divide (1973–74), the largest print ULAE has produced up to this point. This print addresses the flow of water from the Midwest to the East, reflecting Rosenquist’s own trajectory from Minnesota to New York.18 He attends a Senate subcommittee hearing with fellow artist Robert Rauschenberg to lobby for legislation regarding artists’ estate inheritance taxes and resale royalties.

1975

In January, Rosenquist and the artists’ rights advocate Rubin Gorewitz address several hundred artists in Chicago about artists’ royalty legislation.19 Rosenquist designs a set for Deuce Coupe II, a dance choreographed by Twyla Tharpe and performed by the Joffrey Ballet at City Center, New York, in the spring. Rosenquist and his wife, Mary Lou, divorce.

Rosenquist working in original ground floor studio of his home in Aripeka, Florida, 1977. Works shown, left to right: Evolutionary Balance, Gears, and Highway Trust (all 1977). Photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni.

1976

Rosenquist continues to travel back and forth between Tampa and New York, eventually purchasing land in Aripeka, Florida, forty-five miles north of Tampa on the Gulf of Mexico, on which he begins building a house with the assistance of architect Gilbert Flores. Shaped like a bow, the house is propped atop eighteen-foot-high stilts, which accommodate an open-air studio beneath the house.20 Rosenquist continues to acquire land adjacent to the original property, maintaining the natural state of dense, tropical vegetation.

Rosenquist works on Calyx Krater Trash Can, a limited-edition sculpture commissioned by the New York jeweler Sid Singer. This artwork is a small, hand-wrought, solid-gold garbage can that is fabricated and colored with oil paint by Rosenquist and etched by Donald Saff. It registers opposition to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s decision to deaccession works from its permanent collection to finance the purchase of a Greek calyx-krater. Rosenquist is commissioned to create a mural for the new Florida State Capitol in Tallahassee. After Rosenquist’s friend Russian artist Evgeny Rukhin dies (allegedly assassinated by the KGB), Rukhin’s wife moves to the United States and asks Rosenquist to store her late husband’s canvases, which he does at his New York studio.

In June Rosenquist lobbies Congress with Marion Javits—wife of New York Senator Jacob Javits—and Robert Rauschenberg for legislation to permit artists to take deductions on their taxes for the market value of their artworks donated to nonprofit, educational, and other institutions; Rosenquist and Rauschenberg also attend a press conference organized by Senator Javits on the issue. In August the Senate passes Javits’s amendment to the 1969 Tax Reform Act, allowing artists to receive equitable tax credit for their donations valued at up to twenty-five thousand dollars.21

1977

At the invitation of Joan Mondale, the incoming Vice President’s wife, Rosenquist attends the inauguration of President Jimmy Carter. Rosenquist purchases a five-story building on Chambers Street in New York, which he converts into studio and residential space. He produces the etching series Calyx-Krater Trash Can Suite at Pyramid Arts, Ltd., in Tampa, which relates to Calyx Krater Trash Can from 1976. Rosenquist begins working with Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, producing three lithographs, two of which include attached elements.

Rosenquist standing with F-111 (1964-65) at the 38th Venice Biennale, Italy, 1978

1978

Joan Mondale asks Rosenquist to serve on the National Council on the Arts. He is appointed by President Jimmy Carter to a six-year term at the organization, which advises the National Endowment for the Arts. He travels to Venice to attend the thirty-eighth Venice Biennale, in which F-111 (1964–65) is installed. Rosenquist completes a monumental diptych titled Tallahassee Murals (1976–78), featuring symbols of Florida’s industry, economy, and natural environment including the state seal, the state bird (the mockingbird), a monarch butterfly, an alligator, a phosphate rock, palm and pine trees, cattle, crustaceans, and a cowboy hat.22

1979

Rosenquist designs posters for the Institute of Arts and Urban Resources in Queens, New York (P.S.1); the Associates of the American Friends of the Israel Museum; and the inauguration of President John Brademas of New York University. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida, hosts James Rosenquist Graphics Retrospective, the first comprehensive survey of Rosenquist’s prints.

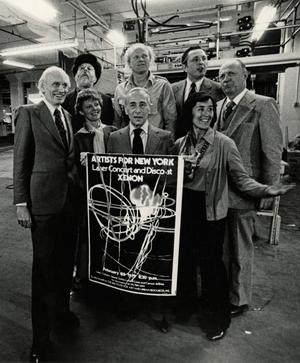

Group at press proofing of Rosenquist's poster for Artists for New York, a laser concert and disco benefit for the Institute of Art and Urban Resources, Inc. (P.S.1) includes Billy Klüver, Henry Geldzahler, Rosenquist and Leo Castelli. Photo by Harry Shunk

Rosenquist and Joan Mondale, Chambers Street studio, New York, 1980.

1980

Rosenquist participates in a conference, the Business of Art and the Artists, at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Small Business Administration. He travels to Israel with Judith Goldman and Carolyn Alexander to give a lecture on printmaking at an exhibition sponsored by the United States Information Agency: Print Publishing in America.23 At his Chambers Street studio, Rosenquist paints Star Thief, whose dimensions, seventeen-by-forty-six feet, will become a standard for a number of later Rosenquist works. The creation of the painting—from blank canvas to completed work—is documented by photographer Bob Adelman over a period of five weeks; in February 1981 the photographs will be featured in an eleven-page color article in Life magazine entitled “Evolution of a Painting.”

1981

In January, Star Thief (1980) is exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, and is subsequently selected by the Dade County Art in Public Spaces Committee for installation in Terminal Two of Miami International Airport. The painting is not installed in the concourse due to resistance from Eastern Airlines—the main tenant of Terminal Two—when Frank Borman, former astronaut and chairman of Eastern Airlines, strongly rejects the painting. A private collector in Chicago (Burton Kantor, a tax attorney) will eventually purchase the painting for an undisclosed sum. (The painting

is ultimately acquired by the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, for the permanent collection.) Rosenquist receives an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University of South Florida, Tampa. He produces The Glass Wishes series of aquatints at Gemini G.E.L.

1982

The La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art in California presents Castelli and His Artists: Twenty-five Years, which is organized by the Aspen Center for the Visual Arts, Colorado, and features work by eighteen artists including Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. In New York the Leo Castelli Gallery mounts New Works by Gallery Artists, which includes paintings by Rosenquist.

1983

In March construction is complete on a large, naturally lit studio on Rosenquist’s property in Aripeka, Florida. His lithograph Ice Point—which incorporates a slivered image of a woman’s face on a starry white background—is published by Visconti/Laxo Vujic in the portfolio Art and Sport to commemorate the upcoming 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia.

1984

Alex von Bidder, Paul Kovi, and Tom Margittai, owners of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building, New York, commission Rosenquist to create a painting in honor of the restaurant’s twenty-fifth year of service. The resulting seven-and-one-half-by-twenty-four-foot painting Flowers, Fish and Females for the Four Seasons (1984) is installed in the east corner of the Pool Room, the restaurant’s main dining room. The French automobile manufacturer Renault Automobile Co. commissions Rosenquist to paint a mural for the Fondation l’Incitation, Paris; Eau du Robot (1984) is Rosenquist’s response.

Rosenquist with Fish, Flowers and Females for the Four Seasons, 1984, while it is being transported into the Seagram Building, New York, 1984

1985

The Denver Art Museum organizes the retrospective James Rosenquist: Paintings 1961–1985, curated by Dianne Perry Vanderlip. The exhibition travels to the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; the Des Moines Art Center; the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Rosenquist completes Sunshot, a mural commissioned for the lobby of the Ashley Tower in Tampa, Florida.

1986

The Scull Collection, including Rosenquist’s Portrait of the Scull Family (1962) and F-111 (1964–65), is sold at Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Auction on November 11 and 12. Sold for just over two million dollars, the highest amount ever paid for a Rosenquist work at auction up to that point, F-111 is subsequently installed in the lobby of the Society Bank tower in downtown Cleveland. Rosenquist creates the mural Ladies of the Opera Terrace, which is a commission for the Opera Terrace, a ballroom located within the Operakällaren restaurant at Stockholm’s opera house.24 He is

also commissioned to paint a mural for AT&T Headquarters in Manhattan. When the painting, Animal Screams (1986), is finished, AT&T abandons the commission, and the work is sold to a group of businessmen in Sweden.

1987

Rosenquist finishes the print series Secrets in Carnations, at Graphicstudio/University of South Florida, Tampa. Begun in 1986, the series comprises five prints—including The Kabuki Blushes—that incorporate interspliced or “crosshatched” images of women and plants. In April, Rosenquist marries painter and writer Mimi Thompson. Representing the Florida Department of State and the Florida Arts Council, Secretary of State George Firestone presents Rosenquist with the Florida Arts Recognition Award on May 6. Rosenquist completes the mural Welcome to the Water Planet, which is a commission for the Corporate Property Investors building in Atlanta. He begins working on a related series of nine lithographic and handmade-paper-pulp works at Tyler Graphics Ltd. in Bedford Village,

New York. At Graphicstudio he likewise creates the related large-scale aquatints Welcome to the Water Planet and The Prickly Dark, which use a grisaille palette to great effect.

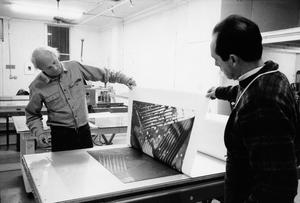

Rosenquist and Bill Goldston working on The Persistence of Electrons in Space at Universal Limited Art Editions, West Islip, New York, 1987.

1988

Rosenquist receives the Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement, Nashville, on July 2. To fulfill a commission from McDonald’s Swedish Corporation, Rosenquist paints the mural Welcome to the Water Planet III. Leo Castelli Gallery features Rosenquist’s seventeen-by-forty-six-foot painting Through the Eye of the Needle to the Anvil (1988) in an exhibition of the same name.

1989

In November, Rosenquist’s daughter, Lily, is born in New York. He completes the Welcome to the Water Planet series with Kenneth Tyler at Tyler’s new studio, Tyler Graphics Ltd., in Mount Kisco, New York. On Rosenquist’s property in Aripeka, Florida, construction is completed on his second naturally lit studio, which incorporates steel girders and corrugated-metal walls approaching industrial scale. He adapts a mobile hydraulic lift to work at various heights on large-scale canvases.

Rosenquist with his wife, Mimi Thompson, with their newborn daughter, Lily, Chambers Street studio, New York, 1989

Rosenquist's staff and studio assistants, left to right: Tony Caparello, James Dailey, Beverly Coe, Bill Molnar, Paul Simmons, Tim Merrill, Cindy Hemstreet, and Michael Harrigan, Aripeka, Florida, 1990

1990

Vandals slash a Rosenquist painting as well as a Roy Lichtenstein painting on view in art dealer Leo Castelli’s booth at the International Art Fair FIAC in Paris. Castelli does not press charges. F-111 (1964–65) is included in High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which is curated by Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik.

1991

In February the State Tretiakov Gallery, Central House of Artists, Moscow, hosts Rosenquist: Moscow 1961–1991, an exhibition organized by Donald Saff. This major retrospective is one of the first post-Cold War exhibitions in Russia of work by an American artist. IVAM Centre Julio González, Valencia, Spain, presents the large-scale painting exhibition James Rosenquist. Rosenquist’s work is represented in The Pop Art Show at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Works included in the exhibition are Hey! Let’s Go for a Ride (1961), I Love You with My Ford (1961), Look Alive (Blue Feet, Look Alive) (1961), and Star Thief (1980). Rosenquist is awarded the Florida Prize by The New York Times Regional Newspapers on June 27.

Rosenquist: Moscow 1961-1991, State Tretiakov Gallery, Central House of Artists, Moscow, 1991

Rosenquist wearing the mask he designed for the Outsiders Masked Ball benefit auction, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, 1992

1992

Rosenquist is awarded the Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by Jack Lang, French Minister of Culture. Gagosian Gallery, New York, hosts the exhibition James Rosenquist: The Early Pictures 1961–1964, in which Rosenquist for the first time displays a small number of his preparatory collages for paintings. The collages are also published for the first time, in the exhibition’s catalogue. He is represented in the exhibition Hand-Painted Pop: American Art in Transition, 1955–62 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. A limited number of Rosenquist’s preparatory collages are shown in this exhibition as well, and are reproduced in the accompanying catalogue. Rosenquist begins painting the series Gift Wrapped Dolls (1992–93),25 which the artist describes as a response to the AIDS crisis. In the

fall the Gift Wrapped Dolls paintings are featured in the exhibition James Rosenquist: Recent Paintings at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris. He completes the monumental print Time Dust, measuring approximately seven by thirty-five feet.

1993

Organized by Constance Glenn at the University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach, the exhibition James Rosenquist: Time Dust, The Complete Graphics, 1962–1992, opens at the first of its ten venues: the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. It is accompanied by an exhibition catalogue that includes a catalogue raisonné of Rosenquist’s graphic works and also illustrates many of his preparatory collages. On March 13 hurricane-strength winds and a tidal surge on the Gulf of Mexico from a tropical storm flood Rosenquist’s Aripeka, Florida, studio and office. Much of the artist’s archives, including documentation, photographs, and works on paper, is damaged or lost. In the spring Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, features Rosenquist’s series Gift Wrapped Dolls (1992–93), along with his painting Masquerade of the Military Industrial Complex Looking Down on the Insect World (1992), in a solo show. Rosenquist’s Gift Wrapped Dolls are also featured in solo shows at Akira Ikeda Gallery, Tokyo, and Feigen, Inc., Chicago.

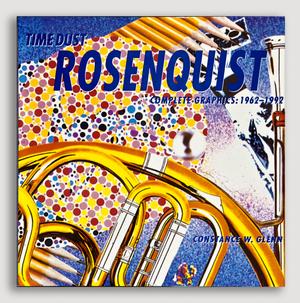

Cover of the exhibition catalogue/catalogue raisonné Time Dust, James Rosenquist: Complete Graphics, 1962-1992 by Constance Glenn, 1993

1994

Rosenquist receives the Skowhegan Medal of Painting from the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine. In the fall Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, celebrates its long connection with Rosenquist by presenting James Rosenquist: The Thirtieth Anniversary Exhibition.

1995

The exhibition James Rosenquist Paintings is shown at the Seattle Art Museum. Rosenquist’s recent work is also featured in Italy in James Rosenquist: Gli anni novanta, a solo show at the Civico Museo Revoltella, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Trieste.

Reunion of artists and others associated with Graphicstudio/University of South Florida, Tampa, at opening of Graphicstudio: Contemporary Art from the Collaborative Workshop at the University of South Florida, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1991. Left to right: Frank Borkowski, Nancy Graves, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Donald Saff, Rosenquist, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Ruth Fine, Robert Fichter, Charles Hinman, Philip Pearlstein, unidentified man, Oscar Bailey, Alan Eaker, J. Carter Brown, and Jim Dine

1996

Rosenquist’s collaboration with Graphicstudio/University of South Florida, Tampa, is honored in the exhibition James Rosenquist: A Retrospective of Prints Made at Graphicstudio 1971–1996, installed at the College of Fine Arts, University of South Florida. In the spring Rosenquist is featured in a solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York. He creates a series of twenty-six gun paintings, which are featured in the spring in the exhibition Target Practice: Recent Paintings by James Rosenquist at Feigen, Inc., in Chicago.

Rosenquist designs a set of six espresso cups and saucers for Italian coffeemaker Illycaffè, which are introduced in late April as the Italian Riviera collection. The cups are decorated with a motif of colorful paper strips, described by the artist as “colored pieces from a straw hat.”26 In November he begins discussions with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, for a mural commission of “an updated version of F-111.”27

1997

Rosenquist receives an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts degree from Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, on May 24. The Center for Contemporary Graphic Art and Tyler Graphics Archive Collection of Fukushima, Japan, host The Graphics of James Rosenquist. In the fall, in New York, he is included in the celebratory Leo Castelli Gallery exhibition Forty Years of Exploration and Innovation: The Artists of the Castelli Gallery 1957–1997, Part One. He begins the Guggenheim commission—requested for the new Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin exhibition space—in his Aripeka, Florida, studio and completes one of the three paintings that constitute this three-part installation work entitled The Swimmer in the Econo-mist (1997–98).

Rosenquist’s Horizon Home Sweet Home is shown in the exhibition Home Sweet Home/Einrichtungen/Interieurs/Möbel at the Deichtorhallen Hamburg from June 20 to September 28.

The Swimmer in the Econo-mist, 1997-98, in progress in the studio, Aripeka, Florida, 1997

Rosenquist applying painted footprints to the 24-by-133-foot painting Celebrating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Eleanor Roosevelt, 1998, with help from studio assistant Darren Merrill, Aripeka studio, Florida, 1998.

1998

Rosenquist paints Celebrating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Eleanor Roosevelt in response to a commission from the city of Paris for a mural to mark the anniversary; it is intended for installation on the ceiling of the Palais de Chaillot, a government building, but remains in the artist’s collection after a change in city leadership. He completes the three-painting suite The Swimmer in the Econo-mist (1997–98), which is installed in the spring at Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin as the institution’s first commissioned work and second show. The exhibition space is located on Unter den Linden, in former East Berlin, on the ground floor of Deutsche Bank’s offices, and the exhibition celebrates the cooperative endeavor between Deutsche Bank and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The subjects of The Swimmer in the Econo-mist are industry, consumerism, and the turbulent nature of the economy as a whole. The painting also refers to the wars that shaped the twentieth century, as the images borrowed from F-111 (1964–65) and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) suggest. Hugo Boss designs and produces an edition of 250 “Rosenquist” paper suits in conjunction with the show.

1999

In the fall Rosenquist is represented in the exhibition The American Century: Art and Culture 1900–2000 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. He begins relatively abstract paintings for the Speed of Light series, which he will work on until 2001. At ULAE he produces a related series of prints with imagery derived from the paintings.

2000

In June, with wife Mimi Thompson and daughter Lily, Rosenquist attends the Friends of Art and Preservation in Embassies reception hosted by Hillary Clinton at the White House, along with fellow artists Ellsworth Kelly, Joel Shapiro, and Frank Stella. Rosenquist’s seven-color lithograph The Stars and Stripes at the Speed of Light (2000) is unveiled at the reception. He donates the edition of fifty to American embassies around the world. Among the artists participating in the program are Louise Bourgeois, Roy Lichtenstein, Maya Lin, Robert Rauschenberg, and Stella.

2001

In the spring Rosenquist travels to Paris, where his work is included in the exhibition Les Années Pop: 1956–1968 at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou. Gagosian Gallery, New York, hosts the solo show James Rosenquist: The Stowaway Peers Out at the Speed of Light at its Chelsea space, which features paintings from the Speed of Light (1999–2001) series. He is also represented in the Gagosian exhibition Pop Art: The John and Kimiko Powers Collection at the gallery’s Madison Avenue location. In June at the Tampa Museum of Art, Rosenquist is inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame. The thirtieth artist or performer thus honored, he joins a group including Jimmy Buffett, Ray Charles, Ernest Hemingway, Zora Neale Hurston, Robert Rauschenberg, Burt Reynolds, and Tennessee Williams.

Rosenquist in Paris, 1989

It Heals Up: For All Children's Hospital, 2002 Polyurethane enamel on fiberglass-covered aluminum 108 x 480 x 84 in. (274.3 x 1219.2 x 213.4 cm) A thirty-three-foot-long fiberglass adhesive bandage on the exterior of All Children's Hospital at The University of South Florida's All Children's Medical Research Center

2002

Rosenquist donates a large sculpture to the All Children’s Hospital, University of South Florida, Saint Petersburg. Affixed to the outside of the hospital’s state-of-the-art Children’s Research Institute, the aluminum and fiberglass sculpture, shaped like an adhesive bandage, is decorated with a colorful motif of a rainbow, a tic-tac-toe game, and various figures and numbers.28 Dedicated in a ceremony on April 23, the sculpture is the second public art project Rosenquist has completed in Florida. He receives an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, on May 19. In June the Fundación Cristóbal Gabarrón of Valladolid, Spain, confers upon him its annual international award for art in recognition of his great contributions to universal culture. In the fall he is included in Surrounding Interiors: Views inside the Car, organized by Judith Hoos Fox at the Davis Museum and Cultural Center at Wellesley College, Massachusetts. Rosenquist signs the “Not In Our Name Statement of Conscience” petition coordinated by the Bill of Rights Foundation to protest the military actions of the United States government in response to the events of September 11, 2001. Among the forty thousand signatories are prominent actors, artists, and political activists. The statement is published throughout the fall and winter in major newspapers across the United States and abroad, including The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian (London), The Daily Star (Beirut), and La Jornada (Mexico City).

2003

In the spring the full-career exhibition organized by the Guggenheim Museum, James Rosenquist: A Retrospective, opens at The Menil Collection and The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, and travels to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain; and Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany, through 2005. Writer Ingrid Sischy profiles Rosenquist in a ten-page article, “Rosenquist’s Big Picture,” in the May issue of Vanity Fair. Rosenquist receives an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts Degree from Montserrat College of Arts, Beverly, Massachusetts. He designs a second limited-edition ceramic coffee cup collection for Italian coffeemaker Illycaffè titled Coffee Flowers Ideas; this design features a cappuccino cup with imagery of women’s smiling faces interspliced with red coffee beans and white coffee flowers. The exhibition Pop3: Oldenburg, Rosenquist, Warhol opens at the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

2004

Rosenquist’s work is included in two Pop art exhibitions in Europe: Das Grosse Fressen: Von Pop bis Heute at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Germany, and Pop Classics at ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark. In the fall, his painting Untitled (1987) is featured in the exhibition The Flower as Image, at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, in Humlebæk, Denmark.

2005

Rosenquist receives the Legends Award from Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York on April 19. He is bestowed an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts Degree from North Dakota State University, Fargo, on May 13. The exhibition James Rosenquist: Ten Paintings, 1965–2004; Collage, 1987 opens at Givon Art Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel. His painting Untitled (1987) is included in the exhibition Flower Myth: Van Gogh to Jeff Koons at the Fondation Beyeler, in Riehen/Basel, Switzerland. Rosenquist’s second paper suit (released as a limited edition by Hugo Boss in 1998 in dyed Tyvek) is featured in the exhibition Pattern Language: Clothing as Communicator at Tufts University Art Gallery in Medford, Massachusetts, and travels to four subsequent venues.

Rosenquist working on Celebrating the Fiiftieth Anniversary of the Signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Eleanor Roosevelt (1998), Basel, Switzerland, 2006

2006

Rosenquist receives the Lifetime Achievement Award from Polk Museum of Art, Lakeland, Florida, on March 21, where his work is also featured in the exhibition Pop Art 1956–2006: The First 50 Years. The exhibition Welcome to the Water Planet: Paperworks by James Rosenquist opens at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, in the summer. His work is featured in London, England, in the show James Rosenquist, which opens at the Haunch of Venison gallery in the fall. Rosenquist donates a painting to the collaborative sculpture project The Peace Tower, 2005–2006, created by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Mark di Suvero for the 2006 Whitney Biennial. The sculpture project is a reconception of the original 1966 Peace Tower (officially titled “The Artists’ Tower of Protest”) to which Rosenquist and more than four hundred artists contributed artworks in protest to the Vietnam war.

2007

Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition Art in America: Three Hundred Years of Innovation, co-organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Terra Foundation, which opens in February at the National Art Museum in Beijing, China, and travels to Shanghai, and then to Russia and Spain. He begins a new body of work—the Time Blades series—in which he contemplates the concepts of time and existence. Works from the series are featured in James Rosenquist: Time Blades, at Acquavella Contemporary Art, Inc., New York. His work is included in the exhibition Pop Art Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London, England, which travels to the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Germany.

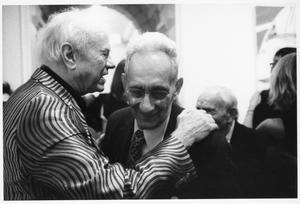

James Rosenquist with Frank Stella at the opening of James Rosenquist: Time Blades at Aquavella Contemporary Art, Inc., New York, 2007

2008

Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition The Story Goes On: Contemporary Artists in the Wake of Van Gogh at MODEM Centre for Modern and Contemporary Arts, Debrecen, Hungary, and in Fernand Léger: Paris–New York at the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, in the summer. His painting on slit Mylar, Daley Portrait (1968), featuring an image of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, is shown in the exhibition 1968: Art and Politics in Chicago at DePaul University Museum in Chicago, Illinois. The early painting Coenties Slip Studio (1961) is presented in the exhibition Circa 1958: Breaking Ground in American Art at Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

2009

On April 25 a brush fire spreads across Rosenquist’s property in Aripeka, Florida, consuming sixty-two of his acres and destroying his house, office, studio, and other buildings. His print archives and numerous paintings are consumed by the flames. Rosenquist moves his office and work space to a stilt-house on the property (located across a road from the area destroyed by fire). He encloses the area under the house to create a studio in which he begins painting again. In October Rosenquist’s memoir, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art, is published by Alfred A. Knopf to positive reviews. The Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, honors him with The Order of Salvador, on November 5. Rosenquist’s painting Tosca—Music, Murder and Mayhem (2009) is shown in the exhibition Something About Mary at The Metropolitan Opera, New York; for the exhibition, he is one of sixteen contemporary artists invited to create work inspired by composer Giacomo Puccini’s 1900 opera Tosca, which opens the The Metropolitan Opera’s 2009–10 season. In sketches and preparatory works on paper, Rosenquist develops the collage Red, White and News for the cover of the holiday 2009 issue of The New York Times Style Magazine.

Aftermath of the fire on Rosenquist's property that destroyed the studio, office, house, and other buildings, in Aripeka, Florida, 2009

Diploma, The Degree of Doctor of Fine Arts Honoris Causa, Corcoran College of Art and Design, Washington, D.C., 2010

2010

Rosenquist’s latest series of work is featured in the exhibition James Rosenquist: The Hole in the Middle of Time and The Hole in the Wallpaper that opens in February at Acquavella Contemporary Art, Inc., in New York City. The exhibition features seven paintings as well as a selection of motorized works, with attached mirrors, that spin. In the spring, he receives an honorary doctorate degree from the Corcoran College of Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenquist’s work is shown in two exhibitions opening at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in September: Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen, and On to Pop. He receives the inaugural Hermitage Museum Foundation Award at the Hermitage Museum Foundation’s first Hermitage Dinner at Christies in New York City on November 6.

2011

Rosenquist begins a new body of work, the Multiverse series, which features imagery of nebulae, star systems, and galaxies and that he will continue through 2015. Two years after the devastating fire on his Florida property, Rosenquist completes the painting The Geometry of Fire (2011), a meditation on the destruction; “The title is ultimately nondescriptive, because there is no such thing as geometry in fire, it’s just wild, totally reckless, an accidental illumination an immolation. Humans always want to inject geometry and meaning into nature, but it’s a mystery.”29 He is recognized as an Alumni of Notable Achievement by the College of Liberal Arts, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis on March 31. Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition Ileana Sonnabend: An Italian Portrait at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy, and in the exhibition Homage to Leo Castelli—9 Works by 9 Artists at the Fundación Juan March in Madrid and in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. The Minneapolis College of Art and Design bestows upon him a Lifetime Achievement Award on September 17. Rosenquist paintings once owned by lifelong friend Robert Rauschenberg—including Spaghetti (1965) and Waiting for Bob (1979)—are featured in Gagosian Gallery’s show, The Private Collection of Robert Rauschenberg, opening in November in New York City.

Installation view James Rosenquist: Multiverse You Are, I Am exhibition, Aquavella Galleries, New York, 2012. Works pictured, on the left: The Geometry of Fire (2011); on the right: Sand of the Cosmic Desert in Every Direction (2012)

2012

The Museum of Modern Art in New York dedicates an exhibition, James Rosenquist: F-111, to Rosenquist’s room installation and historic painting F-111 (1964–65). He completes two prints with etched and rotating mirrors (and with imagery related to the Multiverse series of paintings) at ULAE. Rosenquist’s latest series is featured in the show, James Rosenquist: Multiverse You Are, I Am, that opens in September at Acquavella Contemporary Art, Inc., in New York City. Rosenquist receives the Isabella and Theodor Dalenson Lifetime Achievement Award as part of the National Arts Awards organized by Americans for the Arts in New York City on October 15. His iconic painting, I Love You with My Ford (1961), is included in the Vitra Design Museum’s exhibition, Pop Art Design that travels internationally.

2013

Rosenquist is presented with the ASF Cultural Award at the Spring Gala of the American-Scandinavian Foundation at the Pierre Hotel, in New York City, on April 26 in recognition as one of the founders of American Pop art. North Dakota Museum of Art hosts James Rosenquist: An Exhibition Celebrating His 80th Birthday in Grand Forks, North Dakota, which opens in August. A friend and correspondent to the late artist Ray Johnson, Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition, Correspondents of Ray Johnson, at the Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His work is also featured in the fall exhibition Made in U.S.A.: Rosenquist / Ruscha at the Museum of Art, Washington State University in Pullman. Having exhibited with the gallerist in the 1960s and 1970s, Rosenquist’s early work Volunteer (1964) is included in the exhibition Ileana Sonnabend: Ambassador for the New that opens in December at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2014

Writer Daniel Kunitz and Rosenquist discuss the Multiverse series of works in the article “In the Studio: Master of Space and Time,” in the February issue of Art + Auction. In March, Rosenquist and wife Mimi Thompson purchase a house in Miami, Florida, and set up a working studio there, where he continues working on the Multiverse series. In the spring, Rosenquist’s work is included in the exhibition Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, which travels to two venues in the United States. A selection of paintings from the Multiverse series are shown in the exhibition James Rosenquist: All Things are Devoid of Intrinsic Existence at Wetterling Gallery, in Stockholm, Sweden. Featuring loans from the former collection of the German industrialists Peter and Irene Ludwig borrowed from six different institutions, Rosenquist’s work is presented in the exhibition Ludwig Goes Pop that opens at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne in October, and travels to Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien in Vienna, Austria, in 2015. In November, the focused survey exhibition James Rosenquist: Illustrious Works on Paper, Illuminating Paintings opens at Oklahoma State University Museum of Art, Stillwater, and travels to Syracuse University Art Galleries, Syracuse, New York, in 2015.

2015

Rosenquist is honored as the inaugural recipient of the Spirit of Tomorrow Award by the Women of Tomorrow, Mentor and Scholarship Program, Miami, Florida on March 7. His work is presented in the exhibition, The New York School, 1969: Henry Geldzahler at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, at Paul Kasmin Gallery, in New York City. Rosenquist’s painting Zone (1961) is included in the International Pop exhibition that opens at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota and travels to the Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Rosenquist completes An Intrinsic Existence (2015), the last painting produced as part of his final body of work, the Multiverse series.

An Intrinsic Existence, 2015, Oil on canvas, with a painted and rotatable mirror. 81 x 67 in. (205.7 x 170.2 cm) Private collection

2016

Rosenquist’s painting and room-installation F-111 (1964–65) is the sole work to represent the year 1964 in the Museum of Modern Art’s year-long exhibition, From the Collection: 1960–69, opening in March. On March 31, Rosenquist receives the Lifetime Achievement in Printmaking Award from SGC International during the SGCI Printmaking Conference in Portland, Oregon. In the spring, Rosenquist is the first living artist given a special exhibition at the Judd Foundation in New York City. The exhibition, James Rosenquist, is curated by Flavin Judd and features the paintings Shadows (1961), Yellow Applause (1966), and Time Dust—Black Hole (1992), and the prints Horse Blinders (east) (1972) and Horse Blinders (west) (1972). Rosenquist’s grandchild, Oscar, is born on October 14 to daughter Lily Rosenquist and son-in-law Andrés Altamirano in New York City. In November, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris opens the survey exhibition James Rosenquist: Four Decades 1970–2010 at the gallery’s Pantin location, and James Rosenquist: The Collages 1960–2010 at their Marais location.

2017

James Rosenquist dies on March 31 in New York City. The Museum of Modern Art in New York hosts a memorial service in celebration of his life and artistic achievement on June 26, with speakers including Glenn Lowry, Judith Goldman, Richard Feigen, Frank Stella, John Rosenquist, Agnes Gund (in Gund’s absence, comments are read by her personal curator), Thaddaeus Ropac, Gianfranco Gorgoni, Hilton Als, and Ann Temkin. The survey exhibition James Rosenquist: Painting as Immersion opens at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, in November and travels to ArOS Aarhus Art Museum in Denmark in spring 2018. University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum in Tampa organizes the tribute exhibition, James Rosenquist: Tampa, presenting prints Rosenquist produced at Graphicstudio/University of South Florida and at other local presses including Flatstone Press, Topaz Editions, and Pyramid Arts Ltd, with additional works borrowed from private collections. The museum hosts a memorial service for Rosenquist in commemoration of his life and recognition of his artistic contributions in Florida and beyond on December 2, with speakers that include Sarah Bancroft, Ruth Fine, Peter Foe, Gail Levine, Patrick Lindhardt, Margaret Miller, John Rosenquist, and Don Saff.

Notes

1 See “Biography” in James Rosenquist, exh. cat (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1968), 74.

2 See Peter Schjeldahl, “The Rosenquist Synthesis,” Art in America 60, no. 2 (March–April 1972): 57.

3 See “Special Supplement: A Symposium on Pop Art,” Arts Magazine 37, no. 7

(April 1963): 36.

4 See “Artists for Artists,” New Yorker 39, no. 3, March 9, 1963, 33.

5 Joseph Cornell recorded the visit in a note dated June 25, 1963. See Cornell Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., microfilm, 1056:845.

6 Scull, quoted in Richard F. Shepard, “To What Lengths Can Art Go?” New York Times, May 13, 1965, 39.

7 Doon Arbus, “The Man in the Paper Suit,” New York/The World Journal Tribune Magazine, November 6, 1966: 7–9.

8 See Therese Schwartz, “The Politicalization of the Avant-Garde,” Art in America 59, no. 6 (November–December 1971): 97–105.

9 Schwartz, “The Politicalization of the Avant-Garde.”

10 “The Playmate as Fine Art,” Playboy 14, no. 1 (January 1967): 141.

11 Although this work is often referred to as Fire Pole, that is actually the name of the study erroneously attributed to the larger work.

12 The title and date of Nicolas Poussin’s painting have since been revised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to The Abduction of the Sabine Women (probably 1633–34).

13 See Maurice Tuchman, Art and Technology: A Report of the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1967–1971 (Los Angeles:

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1971), 297.

14 Rosenquist, conversation with the author, February 2003.

15 Rosenquist, “Art Mailbag: James Rosenquist Replies,” New York Times, May 14, 1972, 23–24.

16 See Constance W. Glenn, “Time Dust,” in Glenn, Time Dust, James Rosenquist:

The Complete Graphics, 1962–1992, exh. cat. and catalogue raisonné (New York: Rizzoli in association with the University Art Museum, California State University,

Long Beach, 1993), 66.

17 This work, Capillary Action Ill, is nonextant.

18 See Glenn, “Time Dust,” 62.

19 See Roy Bongratz, “Writers, Composers and Actors Collect Royalties—Why Not Artists?” New York Times, February 2, 1975, sec. 2, 1, 25.

20 See Judith Goldman, “James Rosenquist: Fragments of Fragments,” in Goldman, James Rosenquist, exh. cat. (New York: Viking Penguin, 1985), 67.

21 See Joan Young with Susan Davidson, “Chronology,” in Robert Rauschenberg:

A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 574.

22 See James Rosenquist’s Commissioned Works (Stockholm: Painters Posters in association with Wetterling Gallery, 1990), 17.

23 See Deborah Jordy, “Brief Chronology,” in Goldman, James Rosenquist, 77.

24 See Craig Adcock, “James Rosenquist Interviewed by Craig Adcock, March 25, 1989,” in James Rosenquist’s Commissioned Works, 20, 27–28.

25 Rosenquist’s complete title for these works is The Serenade for the Doll after Claude Debussy, Gift Wrapped Dolls.

26 Rosenquist, quoted in Elaine Louie, “Espresso with an Artist,” New York Times,

late edition, May 2, 1996, sec. C, 5.

27 Judith Goldman, “Swimming in the Mist: Another Time, Another Country,” in

James Rosenquist: The Swimmer in the Econo-mist, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998), 31–32.

28 See Mary Ann Marger, “One Man’s Healing Vision,” St. Petersburg Times, Feb. 10, 2002, sec. F, 8, 10.

29 Rosenquist in conversation with the author, summer 2014; originally published in Sarah Bancroft, “Six Decades of Artmaking,” James Rosenquist: Illustrious Works on Paper, Illuminating Paintings, exh. cat (Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Museum of Art, 2014), 9.

This Chronology by Sarah Bancroft was first published in James Rosenquist: A Retrospective (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2003), and updated by Bancroft for the James Rosenquist Studio website in 2017 and for the catalogue James Rosenquist: Painting as Immersion.